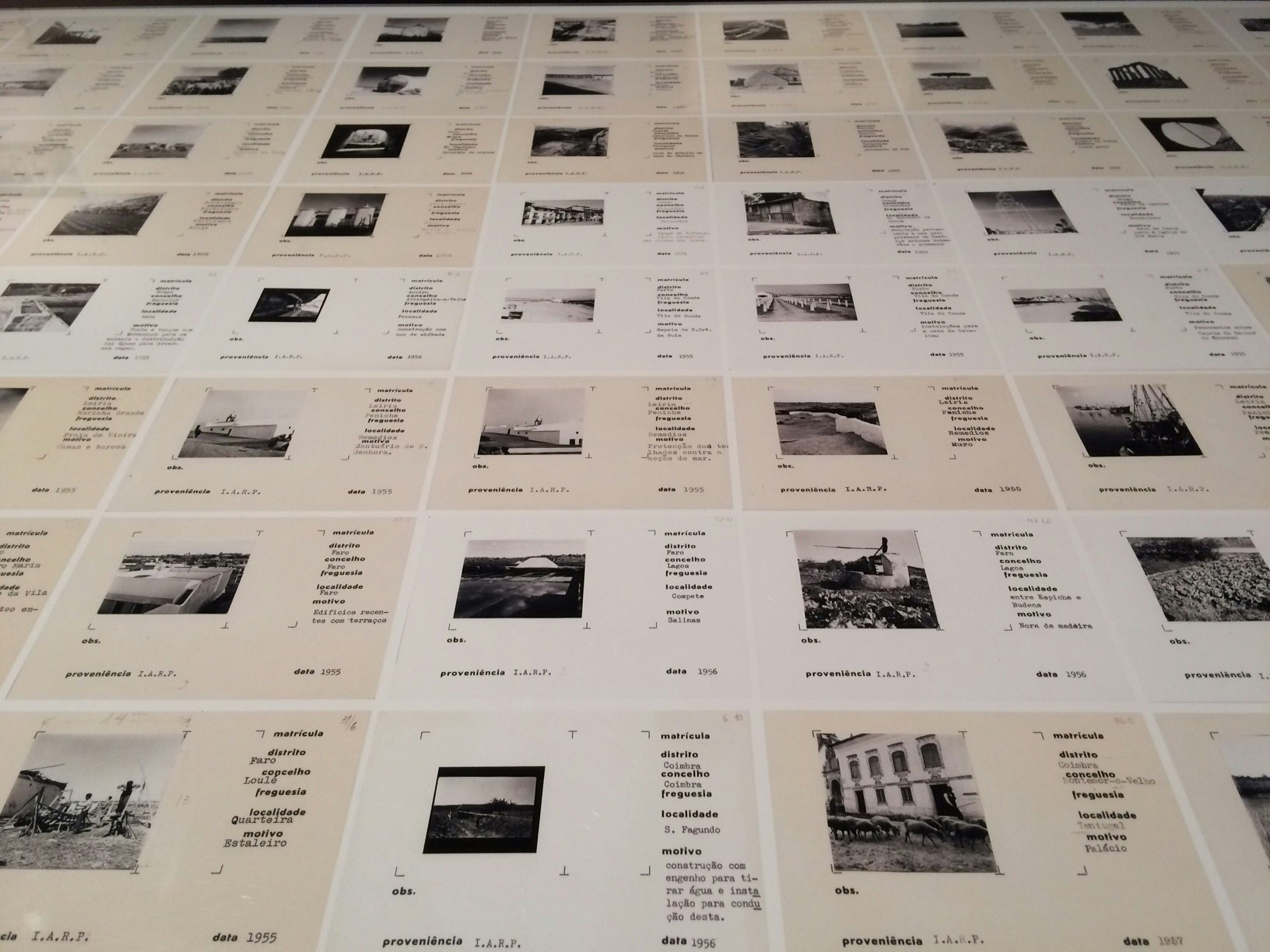

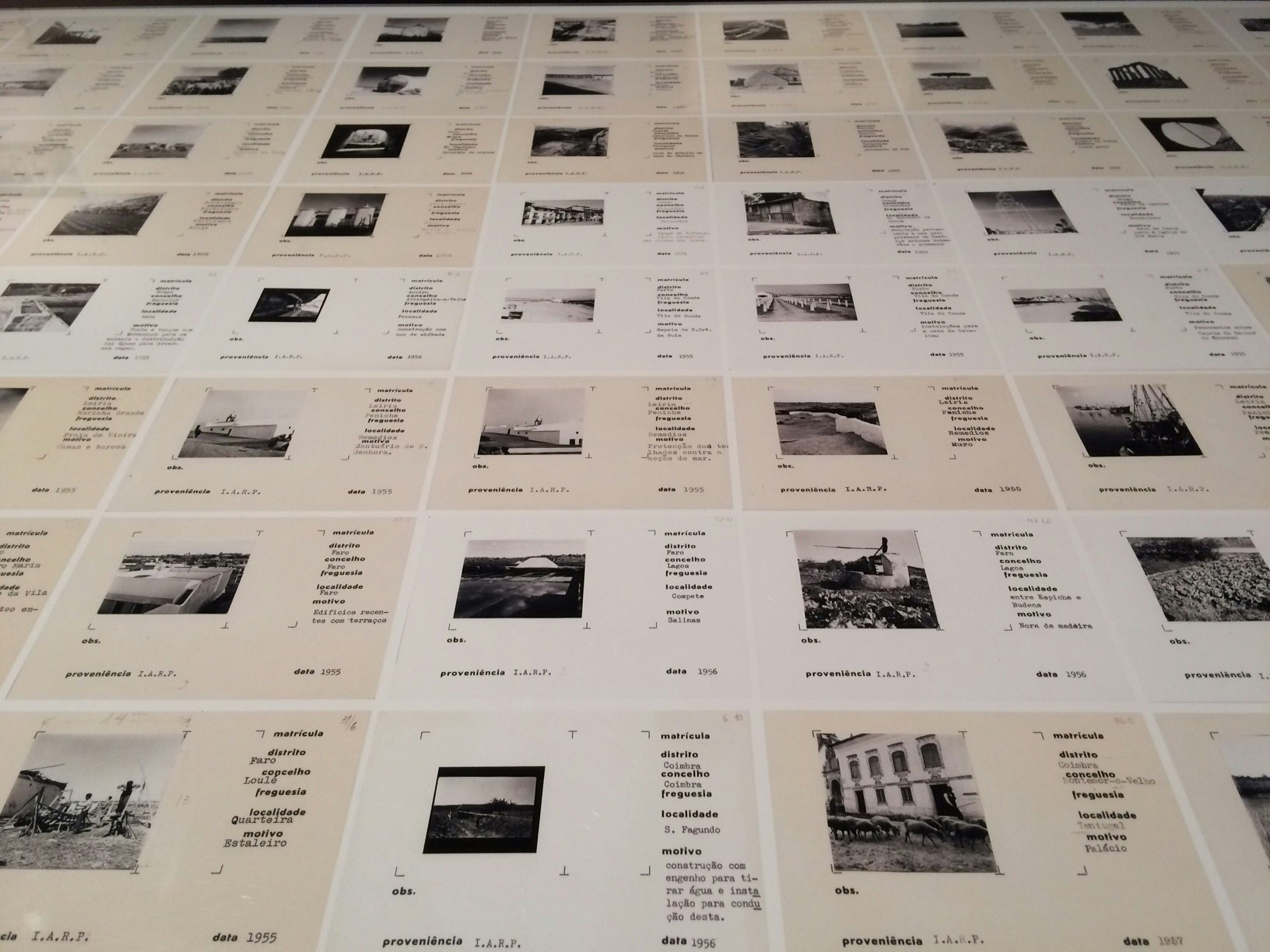

But as I have discussed in previous posts, photographs have ambiguous status in museums, and this is reflected in the way they are put to work. Many, as I have noted

in my first post, are ‘just there’ – transparent, effectively invisible ‘non-collection’ supports for other objects and narratives in which photographs are not articulated as being historical in and of themselves. Thus photographs in museums have multiple and contradictory status and functions balanced uneasily between art and information. They work within the gallery space across several modes – as design solution, as art work, as information, as specimen. All these functions are, given that photography is a medium of both communication and reproducibility, arguably perfectly legitimate – it is not a pure form. But there has to be clarity in how the photographs are functioning at a given moment within the epistemological frameworks of the museum. What kind of knowledge are they producing and how? The

Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin for instance handles this well in my view. Addressing the multiple didactic and aesthetic expectations that audiences have of photographs, there is clear energy yet differentiation to the strands: they could not be confused with one another. Marc Weis and Martin de Mattia’s large lenticular-effect installations (

Was von damals übrig bleibt 1–2 / What is left over from back then 1–2) set the tone with the shifting visions of history as the visitor walks up the stairs. In the galleries photographs are used as information and as design solutions, setting up the ‘economy of truth’ and the ‘feel of the past’ respectively within the didactic narrative. But they are also used as historical objects, such as photographs of facial injury in the First World War and, importantly, presented through historical modes of seeing. This is particularly so the case with stereos where the visitor can see the images, filling their whole field of vision as would have been the case for early twentieth-century viewers.